Cold weather changes everything.

It’s December, and for most of the USA we are heading into seriously cold weather. Cold has a lot of negative effects on off grid power and amateur radio gear. If you have not properly accounted for cold weather, then your equipment will let you down when you most need it. In some cases, lack of cold weather planning can cause expensive damage. Today we’ll discuss the effects of cold temperatures on your equipment and batteries. If you live in an area where it’s always warm, I hope you’ll stick with us anyway and pick up some useful background information.

Radios in the cold.

Most modern radio gear will tolerate cold temperatures quite well. You may notice that in cold weather dials don’t turn easily and switches seem a little heavy. LCD displays may also have a slow/delayed response and batteries don’t last as long as they usually do. Specifications regarding operating ambient temperature tend to be generous on the high end and not so generous on the low end. For example, the Yaesu FT-818 has a specified operating range of 14-140F (-10C to +60C). It’s unlikely you’ll ever see 140F, but 14F is fairly common for many of us.

When bringing radios inside from the cold, some hams insist on letting their gear come to room temperature before turning them on. This isn’t as important as it was in the days when radios had tubes. What modern hams need to be concerned with is condensation. If your radio collects condensation when brought in from the cold, let it dry thoroughly before turning it on. Keep in mind that the guts of the radio will take longer to warm up and disperse water than the outer surfaces. Cold does not kill radios…but water will!

Flooded batteries and cold weather.

It helps to have an understanding of how temperature effects flooded battery chemistry and capacity. A typical, fully charged flooded battery will have an electrolyte density around 1.265 as measured on a hydrometer. What’s important to know is that 1.265 assumes a standard base battery temperature of 80F (27C). To compensate for temperature, subtract 0.004 for every ten degrees below 80F (27C).

For example, you have a fully charged battery with an electrolyte temperature of 50F (10C). Doing the math:

1.265 (measured battery electrolyte density)

-0.012 (0.004 x 3, factoring for the difference between standardized base temp and actual temp)

=1.253 (temperature-corrected density measurement.)

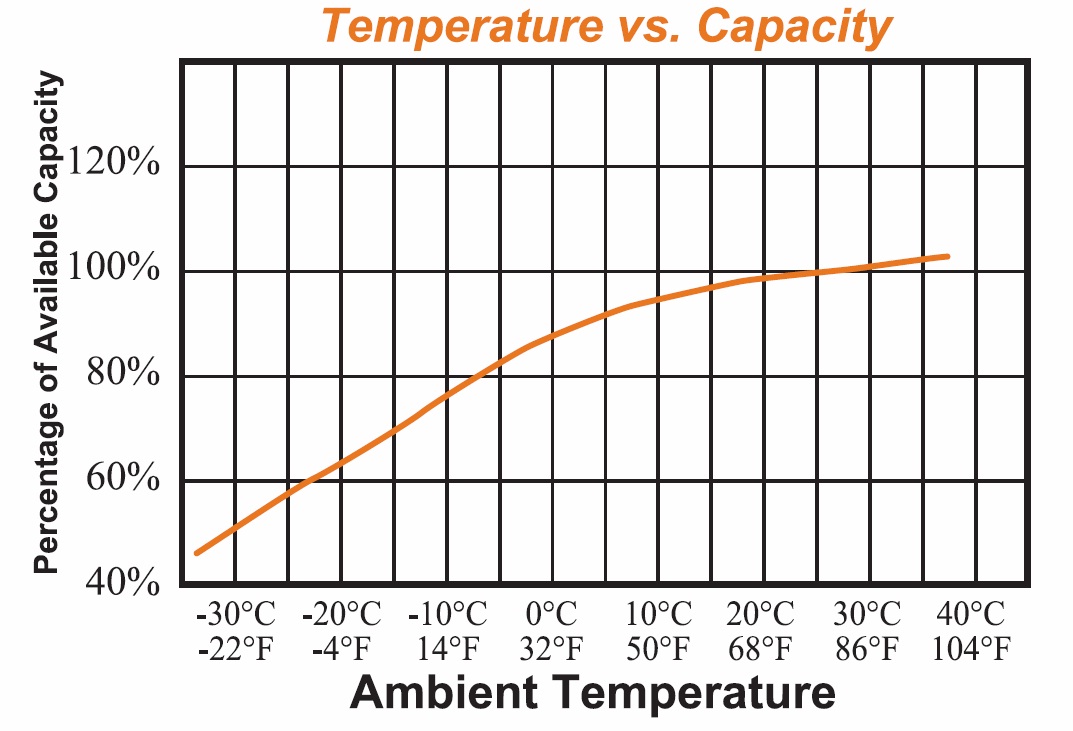

A density of 1.253 translates into about 92%-95% for our otherwise “fully charged” flooded battery at 50F (10C). Referring to the chart below, from 50F on down the drop-off becomes more pronounced. Some solar controllers have a separate temperature probe. This probe attaches to the battery terminal and allows the controller to alter the current or voltage to compensate for the temperature. These devices work, up to a point, but the realities of chemistry cannot be fully negated. In cold weather your flooded battery is simply going to have reduced capacity.

Flooded batteries and the freezing factor.

As the density of electrolyte changes with the charge-dischage cycle, so does its freezing temperature. This has a significant effect on your flooded battery.

The electrolyte in a fully charged battery will freeze around -80F (-62C). You’ll likely never see that, but a discharged battery will freeze around 20F (-7C). Keep in mind these numbers refer to the freezing point of electrolyte, not necessarily the acceptable operating temperatures. Once a battery physically freezes, it’s very likely gone forever.

In cold weather, flooded batteries will take longer to discharge. This may sound like a plus, but remember that you’re losing some of your total capacity due to the cold. It’s a zero sum deal. At the other end of the cycle, cold batteries also take longer to recharge.

Accept that the lower the temperature goes, the longer flooded batteries will take to charge and the less capacity they will have. Keep them as close to the 80F (27C) “sweet spot” as possible.

AGM, SLA, and gel-cell batteries.

I’m lumping absorbed gas mat (AGM), sealed lead acid (SLA) and gel cell batteries together because they are cousins of each other and have similar characteristics.

That said, reliable data on how these batteries react to cold weather is surprisingly hard to find. I did find one study that determined AGM/gel batteries could lose as much as 76% of their capacity at -4F (-20C). The good news is that unless the batteries are physically frozen (which does not happen until about -75F or -60C), they will regain their full capacity once they are warmed up again.

By most metrics, AGM/SLA/gel batteries are not much better in cold weather than flooded versions. Many manufacturers recommend not charging the battery at all if it is below 32F (0C). This of course is a huge problem for many off grid hams. On the upside, small AGM/SLA/gel batteries commonly used by hams are relatively inexpensive. If they need to be replaced every year or so due to abuse, it’s not a big financial outlay.

Here are some tips for using your AGM/SLA/gel battery in cold weather:

- Keep it above 32F (0C) as much as possible.

- Avoid charging when it’s below 32F (0C).

- Use a charger or charge controller designed for AGM/SLA/gel batteries. Many solar charge controllers have user-selectable settings for the various types of batteries.

Lithium batteries.

As with the others, there is good news and bad news regarding lithium batteries in cold weather.

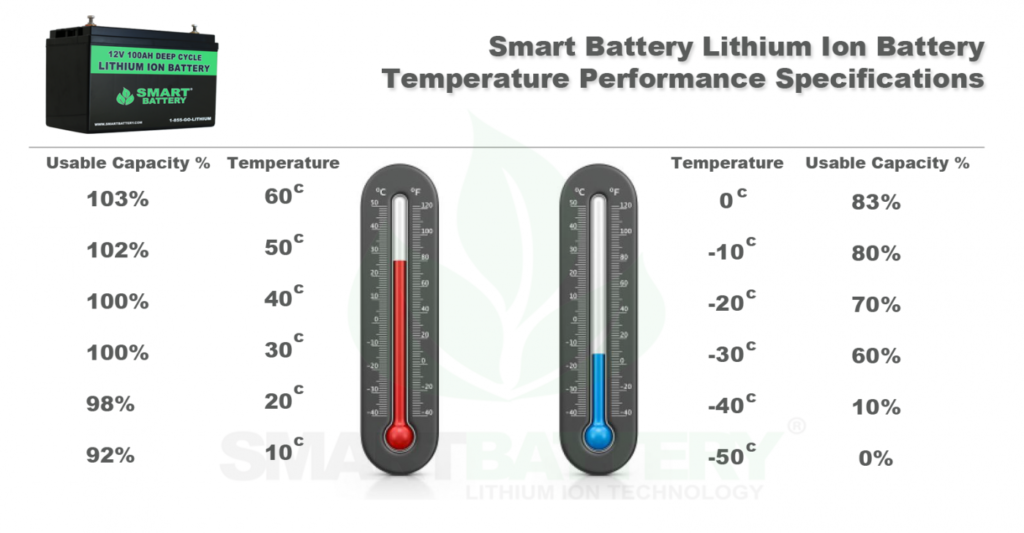

The good news is that they do not exhibit anywhere near the loss of capacity due to cold as the other types. At 32F (0C), a lithium battery will typically give up about 17% of its charge. At -4F (-20C), the typical lithium battery will still have 70% of its capacity. In this regard, lithiums are clearly superior to other types of batteries all the way past 0F (-17C). These factors, plus superior energy density, make lithium batteries a favorite of many hams.

The bad news is that lithium batteries are very easy to damage if they are charged at temperatures below 32F (0C). A phenomenon known as lithium plating can occur during the charging process. The cold causes lithium to collect on the surface of the graphite anode as opposed to being absorbed by it. Once this happens, it is irreversible. A battery can be permanently ruined by charging it cold even one time.

Solutions for charging lithium in the cold.

What can you do? One possibility is to drastically reduce the charging current. While this sounds simple in theory, it’s complicated in practice. Unless your on-battery electronics can communicate with the charger and command it to reduce current in response to temperature, this is not a realistic solution. Still, the technology does exist for those who want to go this way. Even then, you’ll have longer charge times.

A less complicated option is to warm the battery above 32F (0C) before charging. Warm the battery in your car, camper, tent, or even with your own body heat if it is small enough to carry in a pocket.

In my own experience, I’ve found it fairly easy to keep my lithium batteries from getting too cold to charge. I live in the upper midwest/Great Lakes USA area, and trust me, we get plenty of opportunities to test the limits of our gear in cold weather! Although the temperature restrictions on lithium batteries sound very burdensome, with a little forethought it’s not a big challenge.

What we learned today.

- Radio equipment generally tolerates low temperatures as long as it is kept dry.

- Cold weather adversely effects all batteries.

- Electrolyte density in flooded batteries has a temperature compensation factor of -0.004 for every ten degrees below 80F (62C).

- The freeze point of electrolyte varies according to the state of charge.

- Never allow flooded batteries to physically freeze.

- AGM/SLA/gel batteries have a similar cold temperature loss of capacity as flooded batteries.

- Freezing does not cause long term damage to AGM/SLA/gel batteries.

- Cold temperatures do not effect lithium batteries as much as other types of batteries.

- Charging a lithium battery when it is under 32F (0C) can permanently damage it.

- Lithium plating is a condition where lithium bonds to the surface of the graphite anode.

Resources.

This very nice one page list from Canada Battery offers some great AGM battery tips.

NASA produced a very geeky and detailed PDF about lithium plating. This document is nine years old and new developments have come out since then, but the basic concepts presented are still valid.

Here are some previous Off Grid Ham articles that give additional information:

I’m glad for the info on lithium batteries. I had no idea that cold could cause so much harm when charging if the batteries were cold. I remember reading somewhere that electric cars have to have battery heaters and now I know why.

Last year I forgot that my car and truck are both never really turned “off”. There is always some energy drain because of the radio receivers for the keyfobs and keyless entry systems, etc. Both weren’t used for, oh, three months or so, and both had to have their batteries replace in spring. So it cost me about $200+ to learn the lesson that I need to put battery maintainers on both of them over the winter or at least run them on a regular basis.

My lithium cordless power tools are stored in my unheated garage where it can get quite cold in the winter. If I try to charge one of the batteries out there, the charger senses the low temperature and will not let the battery charge until it warms up. If I need my tools for a project then I have to bring the batteries in the house to charge them.

I don’t know if electric cars have battery heaters, but one method to bring batteries up to temperature is to put a modest load on them. The flow of electricity through the natural internal resistance of the battery will produce enough heat to begin safe charging. The car’s computer controls all this and it’s transparent to the driver. For my job I drive a company-provided hybrid car and sometimes in cold weather, especially after the car has been sitting overnight, the instruments will show the battery in discharge mode even though the vehicle is running on gas engine power. I’m not sure but I think this is the computer trying to warm up the battery. After I drive it a few miles, the car switches normally between engine and battery power.

As for your cars being in storage, yes, you should always have a trickle charge even on old cars without “vampire” current drain. My Dad’s 1920 Model T has a maintainer charge on its 6 volt battery. All batteries have some kind of self discharge even when not connected to anything.

Great info, Thanks!

You’re welcome, Dave. Hope you’ll stop by Off Grid Ham again…and tell all your friends!