One of my readers asked about inverter efficiency and suggested that it would be helpful to the Off Grid Ham community if I did an article about overall solar efficiency. Since that’s not the first time the question has been raised, I’ll accept the invite. In this two part series we’ll go through a hypothetical power system step by step and examine solar efficiency, then fit the pieces together to make the picture complete.

Changing your perspective of solar efficiency.

When you buy a car, or a new furnace for your house, or any large appliance, you carefully consider the energy cost and hopefully also the environmental impact of the energy that runs the device. And with rising energy costs, citizens and businesses are looking for ways to reduce the cost of their energy. One way of reducing costs is by switching energy providers. Many businesses are doing this, and you can look here for more information on how you could save hundreds on energy costs.

But you would probably care a lot less about energy efficiency if the fuel was free, virtually unlimited in supply, and emitted no pollution. Who wouldn’t want a dream deal like that? A lot of hams who are considering going off the grid with solar (and some who already have) incorrectly see it that way.

Although the fuel is free, there is a technical and financial cost associated with turning sunlight into useful electricity. We cannot simply overlook the distinction between a household appliance that consumes energy and a solar power system that produces energy. There are two exact opposite dynamics in play here, but the end goal is the same: To get the most out of the input energy.

The point of this little mind bender is to make you think less about the fuel source and more about the process of converting that fuel into something useful. The off grid ham should care about solar efficiency because of the expense and trouble involved with making that conversion, not because of the fuel supply.

The Law of Conservation of Energy.

When we produce energy, we are not really “producing” it. We are only converting it from one form to another. And every time energy is converted or is passed through a physical medium (such as a copper wire) or a device (such as a charge controller), some of that energy is lost, usually in the form of heat.

The catch is that energy cannot be “lost”. It may be turned into a form that is not useful, but it never just disappears. Those who were paying attention in high school physics class will recognize this principle as the Law of Conservation of Energy.

All the energy that ever existed since the universe was created is still out there somewhere. Energy truly is immortal.

What does this mean to the off grid ham?

For the purposes of solar efficiency, we theoretically can get all the free energy we want but our capacity to turn it into electricity is limited because of losses (inefficiency) in solar power systems. Our concern is how much it costs, in both money and technology, to make that conversion. Having an unlimited supply of energy is not helpful if too much of it is lost in the conversion process.

Solar panels: The sun funnel.

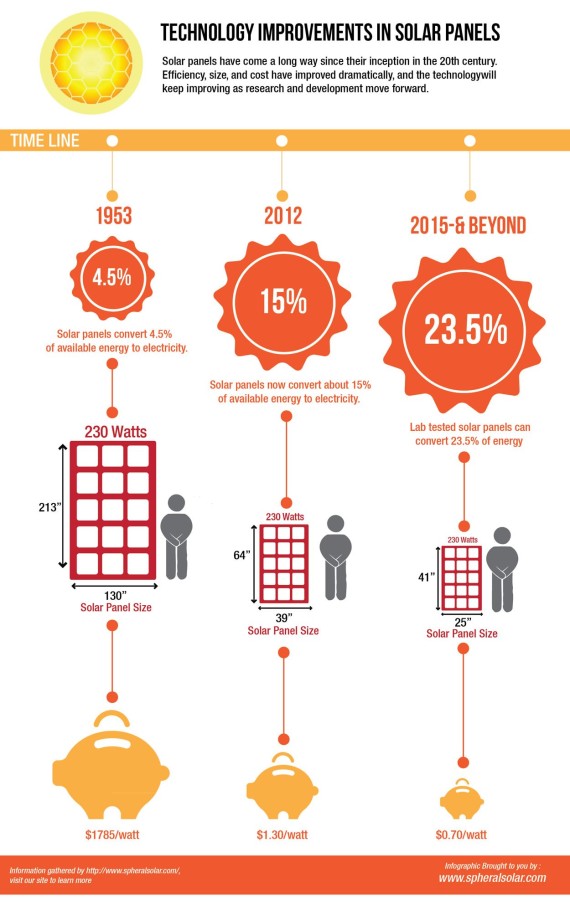

Current solar panels are in the 10%-15% efficient range. That doesn’t look too great on paper, but the sun is so powerful and solar panels are so inexpensive that you can give up 85% of the available energy and easily have plenty left to work with. And the future is looking better: The latest generation panels are testing in 21%-23% efficient range.

What you need to know: Solar panels have a fixed efficiency and there isn’t anything the radio amateur can do to improve it. We have to accept it for what it is. The good news is that panels are so inexpensive that it doesn’t really matter, and their efficiency is greatly improving.

Copper wire feedline: Don’t overfill the pipe.

The feedline that brings the DC power from the panels to the controller is often overlooked as a point of power loss. Unlike solar panels, the off grid ham has a great deal of control over the efficiency of the DC feedline.

The limitations of copper manifests itself on home solar power systems when the feed wires from your panels are too small for the current they are carrying. Energy that cannot be handled by the wire is turned into heat (per the Law of Conservation of Energy), and in a worst case scenario can be a fire hazard.

Solving this problem is simple: Just use the appropriate size wire. This circuit wizard from Blue Sea is a valuable tool for determining what size wire is needed for any application.

One way to increase copper wire solar efficiency is to increase the voltage. This will in turn decrease the current and help you get more out of your wire. Two 12 volt panels wired in series to supply 24 volts has more solar efficiency than the same panels in a 12 volt configuration.

What you need to know: There is no good reason to accept poor DC feedline solar efficiency. Always use the correct size wire and allow for future expansion.

Charge controller tradeoffs.

The charge controller is a common point of solar efficiency loss, and unfortunately, minimizing the loss requires a better, more expensive controller.

There are two types of controllers: Pulse width modulation (PWM) and multi point power tracking (MPPT). Choosing one or the other is a matter of compromises. PWM is inexpensive and simple but not particularly efficient. Expect to lose about 10-30% of your power through this type of controller.

MPPT controllers are a big boost in solar efficiency compared to PWM. They pass over 90% of the input electricity along to your batteries or other load. But MPPT is more expensive and technically complicated than PWM.

Controllers will consume a small amount of power to support their own internal circuitry. This is known as tare power, tare loss, vampire power, or some variation of these terms. The tare loss is usually indicated in the user manual or data sheet. If it is not listed, assume it to be less than two watts.

What you need to know: The main takeaway is that charge controllers contribute to the inefficiency of any solar power system. I won’t go into a lot of detail about the function and types of charge controllers here because I’ve already covered the topic in great detail in this Off Grid Ham article from a few months ago. If you feel a bit lost trying to figure out charge controllers, please refer my previous article and I’m sure you’ll gain a better understanding.

Coming up in part 2 of the Off Grid Ham series Solar Efficiency: It’s Not What You Think, we’ll continue with a discussion about batteries and how they fit into the picture. We’ll also go through a complete solar power system from beginning to end and examine how much energy is lost and what the radio amateur can do to minimize the losses. The series will conclude with some thoughts about the practicality and usefulness of renewable energy.

If there are any questions so far, let me know and I’ll address them as best I can.

Hope you’ll join me next time.

Good article, Chris.

Just like in economics, there’s no free lunch. These photo-voltaic systems incur losses as heat and reduced power delivery at every turn or node, so to speak. And on top of that, the incident radiation swings throughout the year- especially in the northern latitudes. And then you have ambient temps influencing delivered power too. Even using sun power, there’s no free lunch. But extension cords get expensive too. It’s a tough world!

I look forward to Pt. 2, my friend.

Thanks, Mike! Part 1 was mostly conceptual topics; part 2 will be actual numbers and I will show you just how much that “lunch” costs even when the fuel is free. Thanks for your ongoing support of Off Grid Ham.

Nice go at it! Waiting for part 2.

It would be interesting to see, how much of a 150Watt (spec’ed) solar panel will end at one’s 120V lightbulbs after all the inbetween losses.

Also, am I correct that the most important thing to get out of studying efficiency/losses is sizing your battery right?

Hello, and I apologize for the late reply.

In Part 2 we will be going through a solar power system from the panel all the way through to the load and talk about the losses at each step.

As for your battery question, this is also addressed in Part 2. The short answer is that the size of the battery is not necessarily related to efficiency. Battery sizing will effect charge/discharge times, but actual losses are another matter.

I hope you enjoy Part 2. Thanks for being a regular Off Grid Ham reader.

1) I am most concerned with maintenance. That is cleaning of the panels. I have heard that buildup of dirt/dust on panels contributes a significant loss in energy.

For that reason I figure to place my panels in two vertical rows on the side of my house where I have continuous full sunlight. That way with an extension ladder I can easily clean/wash panels.

I can go up about 30 feet.

I am in central California with many farms (therefore much dust in the air).

2) My second concern is to select a good charge controller that will not radiate harmonics and hash into my ham bands. Need to sess out converters at the panels vs. single charge controller/main disconnect.

3) I also figure to not have battery backup, but to rather’ wind back my meter’ only when daily sun gives me power.

I figure the battery pack cost, replacement, maintenance (gas venting, electrode cleaning) weighed against rather constant sunlight in middle California mitigates batteries.

I do have a 5kw gen set that I will convert to natural gas.

All my ham radio equipment runs on repurposed gel cell batteries trickle charged.

Pete W6LAW

================

Hi Pete, and welcome to Off Grid Ham.

1) I clean my panels once or twice a year. In this area we get plenty of rain so the issue mostly takes care of itself. I am not aware of any scientific studies about the effect of debris on solar panels. My guess is that it is negligible, unless of course there is visible dirt as in your case.

2) I’ve heard many hams express concern about charge controllers introducing hash into HF equipment, but I’ve not come across a case of this actually happening. I use a Morningstar Tri-Star 45 amp MPPT controller and have had not had any RFI issues with it. When I have more time I will investigate this problem and possibly do an article on it.

3) To go without batteries and “run your meter backwards” you would need an inverter designed for grid-tie service. You cannot set up a conventional inverter this way, and there are probably permits and building codes involved (especially in California) because you are tapping into the commercial service and are no longer operating “off grid.” Grid tie inverters are quite expensive and should be installed only by highly qualified personnel. I considered doing an article on grid-tie inverters but decided against it since it is outside the main purpose of this blog, but I’ll address the topic if there is enough reader interest.

Thanks again for stopping by Off Grid Ham and for your comments. I hope you’ll become a regular and invite your friends.