It’s hard to follow.

One issue that seems to come up a lot in the off grid radio realm is proper system grounding. The rules and expectations are hard to follow. There are a lot of opinions out there. Many of them are accurate, others are not. Today we’ll go over some basic grounding principles for off grid ham radio. This is by no means a comprehensive guide.

All the same basic grounding concerns with commercial power also apply to off grid energy. Electricity does not behave differently just because it comes from a renewable source. Finally, lightning does not discriminate!

What exactly is “ground”?

In the most simple terms, “ground” is a reference point. If you remember your basic electricity training for your amateur radio license, voltage is an expression of potential energy. However, potential doesn’t mean anything unless it is compared to something. For example, if you are standing on the roof of your house you have potential energy (via gravity) when compared to your yard. If you are laying flat on your back in your yard you have no potential energy compared to the yard because, after all, you’re already in the yard. You can’t fall if you’re already down, right?

Electrical grounding works the same way. Electricity needs a place to go, and it will not go anywhere without potential. Ground provides an electrical reference point. This has many implications for the operational effectiveness and safety of your off grid system.

Grounding outdoor equipment.

If electricity needs a place to go, it’s best for it to have a defined safe path instead of letting it find its own way. Off grid hams should place a high priority on grounding antennas and solar panels.

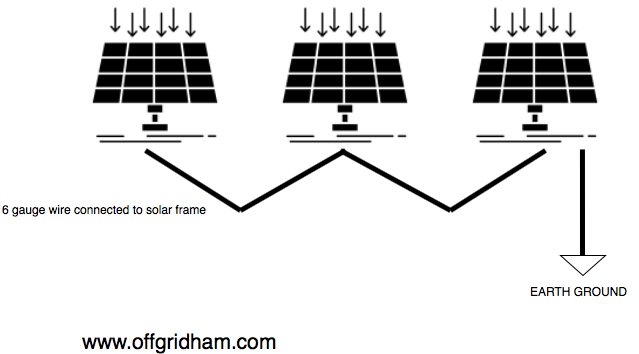

Connect (bond) solar panel frames together with 6 gauge copper wire attached to a conductive metal pipe or rod pounded into the ground. Be sure also to connect any metal support structures. Grounding lugs made specifically for solar panels are available from many sources including (of course) Amazon. Ground rods should be at least six and preferably eight feet deep. Getting a ground rod down that far will be a problem for many hams. You can substitute two or more shorter rods in place of one long one (be sure to bond the rods to each other).

I suggest using a dedicated ground rod for lightning protection on outdoor equipment (solar panels, antennas, etc,). The reason is simple: To minimize the possible paths for lightning to enter your house. Lightning can still come in through coax or the DC cables from your solar panels, but do not purposely create an entrance for lightning if there are other options. Likewise, antenna towers should have their own dedicated ground.

Inverters, solar controllers, and batteries.

On my installation, the inverter connects to a small AC breaker panel. The panel in turn feeds outlets around my house. Grounding is needed on all this stuff. It’s ok to terminate your grounds on a common bus. Remember, do not use the same ground rod as you did for the outdoor equipment.

Properly grounding inverters and charge controllers not only enhances safety, it also goes a long way in reducing or eliminating radio frequency interference (RFI) in your radio gear. Most RFI problems are rooted in poor grounding.

Special note: The National Electrical Code (NEC) Article 690 specifies two key requirements: 1) The negative side of the system cannot be connected to the ground lug of the controller, and 2) The negative side of the system must be earth grounded through a ground-fault device (GFDI) at one (and only one) point.

Not all charge controllers require NEC 690 compliance. It is most common in larger installations. If your controller does not have a ground lug and/or the manual does not give any specific grounding instructions, then don’t worry about it.

Portable generators.

Portable generators are very popular and for the most part plug-and-play. The grounding requirements, where they exist, are fairly straightforward.

Portable generators do not require grounding under the following conditions per OSHA 1926.404: 1) The devices the generator is powering are plugged directly into receptacles physically mounted on the generator. 2) The generator’s gas tank, engine & associated components, housings, and other metal parts are bonded to the generator’s frame. 3) The ground conductor terminals (3rd prong) on the outlets are connected to the generator’s frame.

Probably 95% of radio amateurs’ generators already satisfy these requirements. If you are in this group, your generator is good to go and you don’t have to do anything special regarding grounding.

If you connect your portable generator to a transfer switch, use an external gas tank, or for any reason your generator does not meet all three of the above conditions, then you must have an earth ground on the generator.

Ground loops.

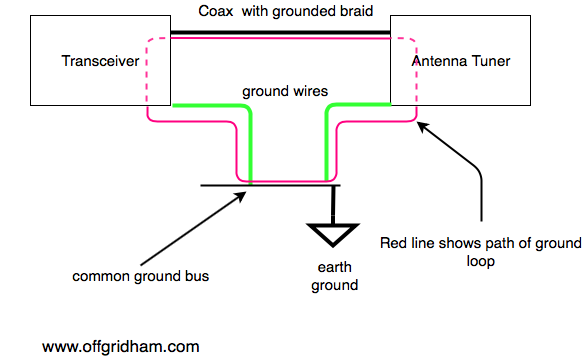

Ground loops come in different forms. A ground loop occurs when you inadvertently create more than one path to ground. Usually this involves grounding two or more devices to a common point, and then connecting the devices to each other.

The diagram below shows a typical ground loop scenario a radio amateur may encounter. How can we break the loop? 1) Remove one of the two ground wires because the devices are bonded via the coax cable anyway (technically will work, but not recommended). Or 2) Have a separate earth ground for each device (preferred). Place the ground rods far enough apart that it does not create another ground loop. Each ground rod can have its own common bus to avoid ground loops in other devices.

The easiest way to avoid ground loops is to make sure there is only one path to ground for each device. This does not mean devices cannot share a common ground bus. It only means you have to make sure there no other interconnections that may create a loop.

Ground loops can act as a path for interference in your receiver, create “hot spots” on equipment enclosures when you transmit, or cause SWR problems. Ground loops do not always cause problems, but if you have them, look for a ground loop as the possible source. It’s certainly possible to have ground loops and experience no anomalies at all. Do not obsess over ground loops. Sometimes they cannot be avoided.

Bonding vs. grounding vs. earthing.

Bonding is connecting two conductive surfaces so that they always have the same potential. As we previously illustrated with our laying in the yard example, if there is equal potential then there is no transfer of energy and therefore greatly reduced risk of electrical shock. Bonding is a safety feature commonly found between metals that do not normally carry current, such as equipment enclosures. Because something is bonded does not by default mean it is grounded.

Grounding is when something is connected to a potential reference point. That point can be the earth, the chassis of a piece of equipment, or simply any other point with less potential.

Earthing is basically grounding without current, or as they say in the business, “connecting the dead part”. When you ground the frame of your solar panel, you are technically “earthing” it because the frame of a solar panel does not normally carry current (“the dead part”). Earthing is a passive function.

In the United States, the term earthing is very uncommon. Grounding and earthing are more or less the same thing in American nomenclature.

What we learned today.

- Among many things, “ground” is an electrical reference point by which all other points in a circuit are compared.

- Outdoor equipment should be grounded such that uncontrolled electrical charges will not enter the building.

- Not all inverters and solar controllers require a dedicated earth ground. Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Portable generators do not require a dedicated earth ground if they meet the criteria set forth in OSHA 1926.404.

- Ground loops occur when there is more than one path to ground.

- Ground loops do not always create negative effects.

- Bonding is when two conductive surfaces are connected together so that they always have the same potential.

- Grounding is when a circuit or system is connected to a point of lesser or no potential.

- Earthing is when a passive conductive surface that normally does not carry current is connected to a ground.

- In the United States, earthing and grounding are essentially the same thing. The term earthing is rarely used.

Thanks Chris! I am new to amateur radio and your articles are a big help!

I’m glad to be of assistance, Dave. I hope you’ll tell all your friends about Off Grid Ham.

Nice article, Chris. Grounding seems to be a mysterious and arcane art for a lot of people and it doesn’t need to be. It can be pretty simple if you understand the way electricity flows and the reasons behind the regulations you need to follow to meet electrical code. For anyone who would like more information I’d like to recommend the ARRL’s book Grounding and Bonding for the Radio Amateur. It’s easy to understand and well worth the $10. When someone asks me about how to deal with grounding that’s the resource I steer them to first.

Note – got a new transceiver! Picked up a Yaesu FT-450D. It was ridiculously cheap, looks and works like brand new. I couldn’t pass it up. Relatively small. Lot bigger than the 818 but still a manageable size, puts out 100 watts, built in antenna tuner and a surprising number of really useful features. I was thinking of using it semi-portable when I want more output than the 818 provides, but the thing is so nice it’s turned into my go-to radio for FT8 and JS8 here in the house. Need to run some numbers and see what kind of batteries I’d need to feed it out in the field for a reasonable amount of time.

Hi Randall, grounding can be a very tricky subject, especially when RF is involved. I’m not a big fan of ARRL books in general, but I do have the Grounding and Bonding book and it is one of the better ones.

Good deal on the 450. It has a lot of bang for the buck. It’s only marginally bigger than the 857D and much more user friendly. I’m sure you’ll get a lot of miles out of it.