Radio amateurs who never drift outside the ham bands and don’t see a need for a scanner receiver to monitor other services are cheating themselves out of a very valuable resource. Not only is monitoring non-ham communications interesting and fun, it can give you a huge advantage in a shit-hits-the-fan (SHTF) situation. Scanner receivers should not be an afterthought; they should be a key part of every ham radio operator’s collection of equipment.

Why do you need a scanner?

Approaching this strictly from amateur radio perspective, no, you don’t need a scanner. But if your ham radio goals include communications intelligence gathering for survival/prepping purposes, or you just want to expand your communications abilities and enjoyment of the hobby, then a scanner is not an accessory, it’s required.

Even if you’re not a survivalist planning for a zombie invasion, simply knowing what is going on in your locale without the filter of traditional and/or social media is useful. On more than one occasion, I’ve heard an incident play out on my scanner only to find a very different version of the same story in the media. Having a scanner is as close to the action as you’ll get without actually being an eyewitness.

When the media can’t be trusted, or when you can’t be sure you’ll even have access to the media, the scanner is an important asset. This is especially true for small, localized incidents that are not particularly newsworthy but mean a lot to those in the immediate affected area.

True story: Late on a Sunday night last fall there was unusual activity on the railroad tracks up the road from my house. A train was stopped and I could see flashing lights from several emergency vehicles over a thick grove of trees. My main concern was that there might be a hazardous materials spill from one of the freight cars.

I turned my scanner on to the frequencies used by the railroad and within minutes discovered that the train had struck and killed a trespasser walking along the dark tracks. I felt bad for what happened but was relieved that it was not a more widespread incident. My scanner helped me ascertain a situation when no other information source was available.

How can I determine what frequencies are used in my area?

This is the most commonly asked scanner question, and thankfully it has a very easy answer. Radio Reference is the go-to source for frequency assignments. It is easily searchable, very well organized, and is updated almost daily. Bookmark the site. There is nothing better.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) also maintains an on line database of all licensees and the frequencies they operate on. Like every government operation, the FCC website is needlessly complex and difficult to navigate. The information is there, but you’ll have to dig for it.

Types of scanners.

There are three types of scanners: Trunking, programmable non-trunking, and crystal controlled. There are also apps for smartphones that let you monitor radio traffic from all over the world via an internet stream.

How trunked radio systems work.

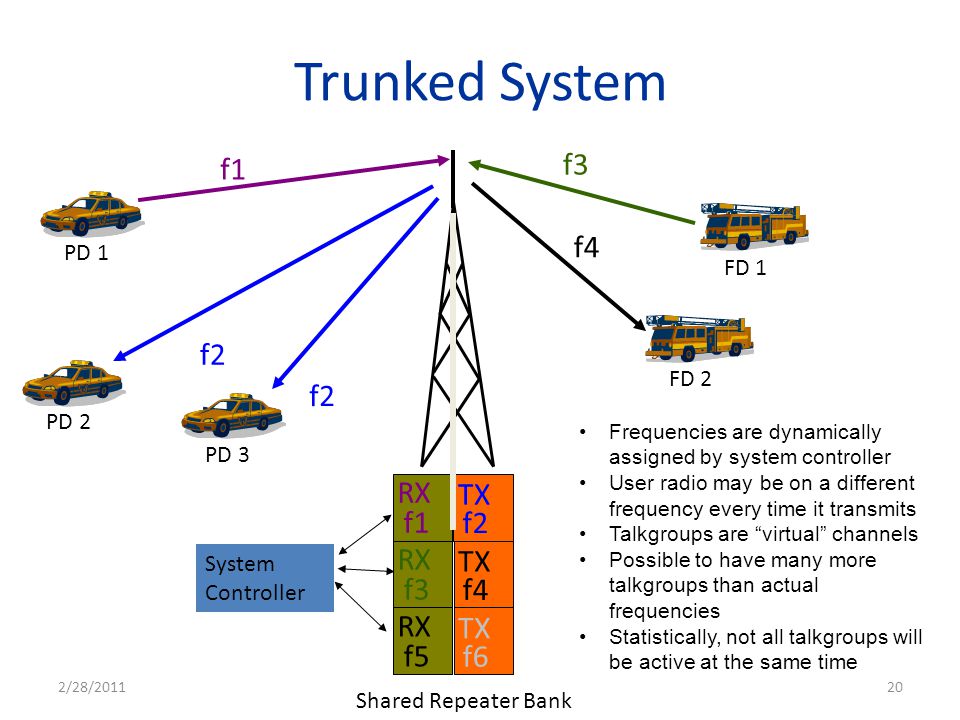

Trunked radio systems are used in larger cities, countywide covering several smaller cities, or anywhere there is a lot of radio traffic. The main purpose of trunking is for many stations or services to share a small number of radio frequencies.

Example: Suppose a city has assigned frequencies in a traditional radio system of fire, police, medical, and municipal services (road crews, water department, school buses, etc). Each service is limited only to their assigned frequency. When there is a lot of activity on one channel, there is no way to move it over to an unused channel designated for another service. You could have a situation where the fire frequency is jammed with emergency traffic while the school bus frequency just sits there silently doing nothing. It’s a very poor allocation of resources.

Trunking fixes this problem. Instead of designated frequencies, each station on the network is assigned to a logical talk group. When any station transmits, a computer system via a control channel automatically chooses a clear frequency and switches every single radio in the talk group to that frequency. This process takes fractions of a second and appears seamless to human users. Any station not in the talk group remains idle and does not hear the transmission, and it is possible that the talk group will change frequency every time a mic is keyed.

A city could create separate talk groups of fire, police, medical, and municipal services, all of which use the same block of frequencies but none of which can hear or interfere with the others. If the fire talk group needs additional capacity, the system can expand to another frequency while still allowing the other groups to carry on as usual using the remaining channels. The built in dynamic network scalability and conservation of bandwidth is what makes trunked systems so popular.

There can also be talk groups subdivided by geography or job function: The police department can have talk groups for parking enforcement, animal control, east and west districts, etc.

Scanners with the ability to follow trunked systems in real time have been around for for many years. In my radio setup I have a Bearcat BCT15X trunk tracking scanner. I’m very satisfied with it even though the programming is somewhat quirky.

Non-trunking scanners.

A programmable standard scanner typically covers the same frequencies as trunk trackers, but without the tracking function. The biggest problem this presents when monitoring trunked systems is that the scanner will not follow the talk group and will pause scanning when it receives any radio signal. This can result in missing transmissions, i.e., you hear one station ask a question but do not hear the other station’s response because the scanner continued scanning and stopped on another unrelated transmission. If you are in an area without a lot of radio chatter, this may not be much of an issue. It’s how scanners worked long before trunking came along. The problem sounds a lot worse than it really is.

Standard non-trunking scanners are very inexpensive. One of my personal favorites is the Uniden BC355N. It is small, has low power requirements, and costs less than $100. The BC355N performs well beyond its price tag. I like mine so much I may get a second one and permanently install it in my truck.

Crystal controlled scanners.

Crystal scanners have been out of production for nearly two decades, but since there are so many of them on the used market and they are worthwhile in some limited applications, I’ll go over them.

A crystal scanner uses plug in crystal modules made for specific frequencies and cannot be programmed. These scanners are usually limited to between four and fifteen channels, and you need a crystal for every single frequency you want to monitor. Scanner crystals are also no longer made, so if you want to use this type of scanner, you’ll have to find one that already has crystals for the frequencies you want, or hunt around at swap meets or on line to find the appropriate “rocks”.

Clean, working crystal scanners can be bought for as little as $5.00. In rural areas that have only a few channels that are not trunked, a crystal based scanner is still useful. They are also handy as a second receiver to monitor specific fixed channels such as NOAA weather statiions. Survivalists & preppers may want to consider acquiring a few crystal scanners set to local frequencies and keep them as SHTF giveaway/loaner/barter items.

Scanner apps for smartphones.

There is a lot to love about smartphone scanner apps. They are free or very cheap, do not require an antenna or extra hardware, and allow you to hear transmissions from cities far beyond scanner range. The downside is obvious: They really aren’t “off the grid.” They depend on the internet, which may not be there when SHTF. And they can also run up your mobile data usage. By all means, try out the scanner apps and have fun with them, but don’t rely on them as your only monitoring method. You’ll still want stand-alone scanner capability not connected to the internet.

Should you get a base or handheld?

Ideally you should have both. Scanners are not so expensive that having more than one is beyond the realm of most radio amateurs. Handheld scanners come in both trunking and non-trunking models and often have the same electronic guts and software as their larger brothers, so there is no inherent performance advantage one way or the other. Where the two formats differ is in the antenna and audio quality, both of which are compromised on a handheld scanner. There is no clear good or bad. I don’t use my handheld scanner a lot, but when I do, it’s very handy.

Scanner antennas.

There are a lot of good base scanner antennas on the market, but if you are monitoring local comms with strong signals you may not need one. Keep in mind that for monitoring the 400-470 MHz UHF and especially the 800 MHz trunked bands, coax loss is not going to be a minor issue. A scanner antenna placed high on your roof may give worse performance than a simple indoor back-of-set antenna after the coax loss is factored in. Refer to this Off Grid Ham article from April, 2016 for a complete discussion of coax cable loss issues.

As for mobile scanner antennas, I’ve never seen a good one. They are mostly “Swiss Army knife” devices, meaning, they do all things, but none of them very well. Instead, I suggest a 2m/440 ham antenna for mobile scanning. It will give excellent results on the VHF/UHF bands, and perform better than most scanner-specific antennas on 800 mHz.

Harris OpenSky: Very bad news for scanner users.

OpenSky is based on a communications protocol invented by M/A-COM and currently marketed by the Harris Corporation to public safety agencies as a replacement for legacy radio infrastructure. It is basically a glorified cellphone system and cannot be intercepted by any scanner. Luckily, there are not that many active OpenSky networks in use, and many of those are being converted back to trunked or conventional radios due to numerous technical problems. Radio Reference will tell you if you are one of the unlucky ones who live in an area where OpenSky is used.

Scanner laws & legalities.

There are laws on the books that vary by state related to the use of scanners. These laws for the most part pertain to scanners in a motor vehicle or other non-fixed application. Most states permit the use of mobile scanners. Some limit use to professionals who need them (such as off duty police or the media) or licensed amateur radio operators. Indiana, Kentucky, Minnesota, Florida, and New York in particular have very strict scanner laws. I’m not sure how many police officers even know about these laws, and when they do, if they care. Use due diligence before hitting the road.

Key points–what you need to know.

- Scanners are valuable for situational awareness and to monitor local events when the news media is unavailable or unreliable.

- There are three types of scanners: Trunk tracking, programmable non-trunking, and crystal controlled.

- Scanner apps for smartphones are ok for what they are, but are not considered “off the grid” because they rely on the internet which may fail in a SHTF situation. Apps should not be your only scanning resource.

- In trunking technology, there are no designated frequencies. Users are instead divided into talk groups. A computer allocates channels on an ad hoc basis. This allows more communications over a smaller number of frequencies.

- Some states have restrictive laws regarding the use of scanners. Do your homework now and save yourself fines & fees later.

Scanners are an often overlooked but important part of off grid ham radio resources. They are inexpensive and relatively easy to use, so there is no good reason not to have one. If you have limited your participation to amateur radio bands only, now is the time to expand your horizons. Survivalists and preppers as well as those who just want to stay in the loop will get a lot of benefit from a scanner.

Thanks much, Chris. Good information, and lots of it. I’ll have to examine the RadioReference link in more detail, for specific data and get hard copies of some info in addition to the bookmarked link. And good info on the scanner technology as well. I’ve saved many of your past posts in hard copy, just in case the internet connection isn’t available and I’ve forgotten some details! 😉

Thanks for your confidence. And printing frequency tables from Radio Reference is an excellent idea I practice myself.

Chris,

the frequencies you mentioned in your text do not make sense. 470 mHz (mili Hertz) and 800 mHz (mili Hertz) are 0.47Hz and 0.8Hz. Maybe there are some very interesting military systems operating at such low frequencies, but reception of these bands requires very big antennas, what makes them completely impractical for scanning.

I assume you meant 470 Mega Hertz and 800 Mega Hertz bands, but then you should have use capital “M” for the prefix: 470MHz and 800MHz. The case of the prefix makes a huge difference: “m” stands for “mili”, which means 10^-3, and “M” means mega, which multiplies the following unit by 10^6. The difference between them is 10^9 times.

Jacek is right, but I am very confident that everyone knew what I was really talking about. Thanks for stopping by Off Grid Ham. I hope you’ll come back again, and invite your friends. The article has been edited to fix the error.

Hi

I enjoyed your site. I am looking for a scanner for my grandson. 11 yr old. He lives in Santa Barbara, CA. Do you have a suggestion?

Thanks so much.

Cindy Harrity

Hi Cindy, I’m so glad you found Off Grid Ham. As for a scanner, some of this depends on your grandson. Many of the new scanners can be tricky to program unless you also buy the software and special interface cable. A great basic scanner that I use myself is the Uniden Bearcat BC355N. It costs less than $100 and does not require any programming. Just push a button and go. Keep in mind the BC355N is not portable. If he wants something he can carry around, the BC75XLT is a good pick. It does require programming, but it’s not too heavy. If he’s more advanced and good with technical stuff, the Uniden BCT15X is awesome. I have one of these too. It’s a great scanner but very tedious to program. If he’s going to program the scanner himself (or someone is doing it for him), then you’ll need a list of active frequencies in your area. For that, I suggest http://www.radioreference.com. It will list everything you need to know. I hope this is helpful, and thanks again for stopping by.

Hi Chris — I’m John – Cindy’s husband, but more important, the Grandpa of the team. Thanks for your quick and educated response to Cindy’s question. I think we will start with a mobile scanner – the Uniden BC75XLT – so our grandson can bring it along in the car and carry it wherever. We are going to get one first and get to know it. Our grandson will be here after Christmas, and hopefully by that time we will have the basics figured out.

I did have one question about the scanner — is it worth getting a better antenna than what comes with it, and do you have any recommendations about which one?

Again, our thanks for your informed guidance so far.

Hi John…the “rubber duck” antennas that come with scanners are not that good, but that’s the trade off for having something small and portable. There are external scanner antennas for cars that attach with a magnet, but they are not much better. I suggest a dual band VHF/UHF ham antenna with a magnet mount. Sometimes these are sold as “2 meter/70 cm,” “144/440,” 2meter/440” antennas or some variation of this nomenclature. You should be able to find one for less than $50. It will work great on that scanner. Make sure you get the correct fitting on the end of the cable. If you get lost in all this, shoot me an email and I’ll help you out.