Graduation time.

A lot of if not most off grid hams have only one battery in their system. Connecting a single battery is more or less self-explanatory. What should you do when you expand your system to include multiple batteries? Should they be in series? In parallel? Is one way “better”? Does it really matter? Let’s take a look at series and parallel battery connection techniques and what it might mean to your off grid power system.

Equality for all.

No matter what connection method you ultimately choose, start out with consistency in your batteries. All the batteries in your system should be the same voltage, amp-hour rating, and type (flooded, AGM, lithium, etc.). If you are buying batteries new, get the same brand and model.

When I’m looking to replace the batteries in my home system, I go one step further. I bring a battery analyzer with me to the dealer and identify a group of batteries that have the same or nearly the same internal resistance and the same manufacturing lot/batch number stamped on them.

It takes time and I have to check many batteries to find a matched set. I’ve found that if I’m polite and explain to the sales people what I want to do (and not interfere with other customers) they will understand and cooperate. You’re making a big investment. If you’re not inclined to be as quirky as me, at the very least check the date code and pick batteries that were made in the same month.

While we’re talking about date codes, choose the most recently-made batteries available. I’ve seen date codes on “new” batteries going back eight months! Batteries will degrade over time, even when not in use. Do you really want a battery that is already more than half a year old when you buy it? And it’s been sitting around all that time (probably) without a float charge?

If you are not buying in person (ie, on line), then you will just have to take your chances. Having a “matched set” is not mandatory, but if you have the opportunity to hand-pick your batteries, you should do so. series and parallel battery connection

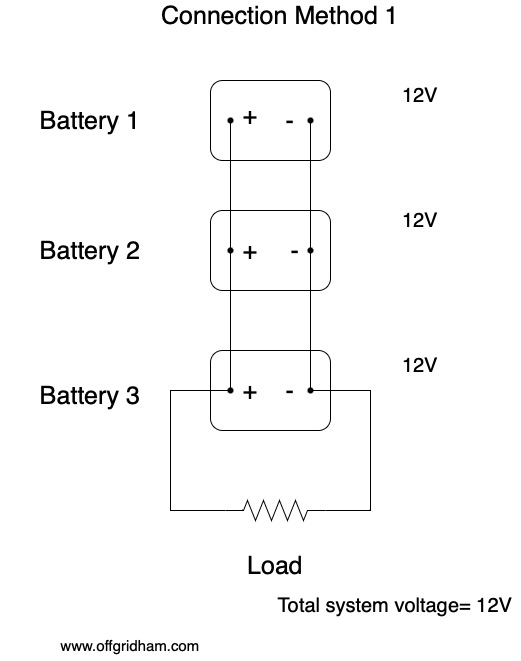

Connection method #1: You can learn from my mistake (or, what not to do). series and parallel battery connection

Years ago when I was young and still learning all this stuff, I set my batteries up with connection method 1. I didn’t think it was a big deal at the time, but it was a horrible idea. Learning from your mistakes is good. Learning from someone else’s mistakes is even better! I urge you to learn from my mistake and not connect your batteries this way.

As shown in the diagram, the batteries are tapped at the positive and negative terminals of the last battery in the string (battery #3). What is wrong with this? The internal resistance of the batteries and connection wire, albeit very small, has an outsized effect on the current draw of each battery. This results in one battery producing significantly more current than the others. Remember, current will always favor the path of least resistance, even if the difference is very small.

Battery #3 will bear most of the load and drain the quickest. As this happens, Batteries 1 and 2 will increase output to make up the difference. No matter what, the batteries will never be balanced (in terms of sharing the load equally) and Battery 3 will have a shorter service life than the other two. As we already discussed, batteries should be installed and replaced as a complete set. So, you’ll be faced with replacing three batteries because one went bad. This method underuses two (or more) batteries while beating one to death.

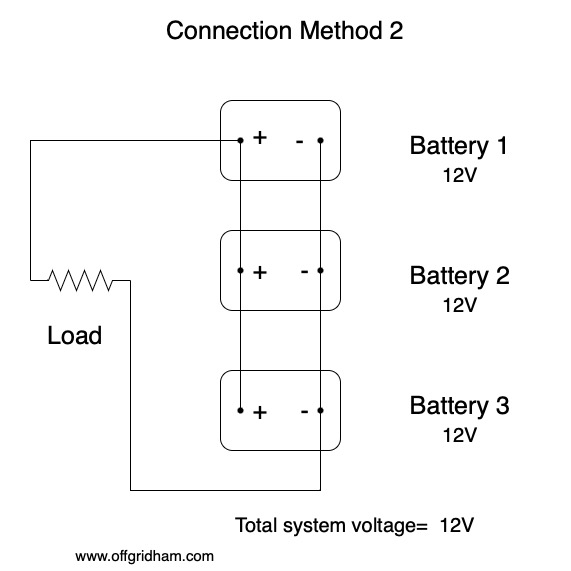

Connection method #2 (waaayyy better!)

After learning my lesson the hard way, I reconfigured my system into Connection Method 2. The batteries are still interconnected the same way as before, except this time the tap for power is taken from each end of the string. series and parallel battery connection

Since the power is being drawn from the positive on the first battery and the negative on the last, it forces the current to travel through all three batteries to form a complete circuit. No one battery is stuck doing most of the work while the others just coast along. The inherent resistances of the batteries and the wire will still cause a more or less negligible imbalance. It’s a huge improvement over Method 1.

My home solar has been connected by this method for many years now. I’ve had no problems and each battery is pulling equal weight.

There is another connection method that is even better than this. However, to me it seems like something for those who are obsessively nit-picky. It’s too much effort for a small gain. There is a link at the end of this article for anyone who wants to look into it further.

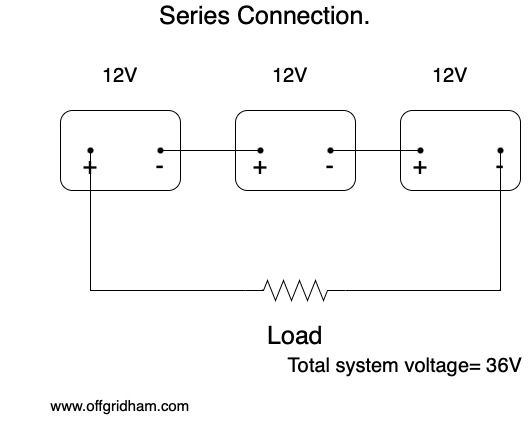

Series connections.

The last connection method is to connect the batteries in series. It’s very straightforward: Connect positive to negative in a “daisy chain” pattern. The power is tapped at each end of the chain. This method is foolproof in that, since the batteries are in series, the current flows equally and the batteries will (mostly) balance the load between them. The principle is very similar to Connection Method 2, above.

There are a few things to consider. First and most obvious, the system voltage will be the sum of all the batteries. So, if you chain three 12 volt batteries together in series, your total voltage will be 36 volts. That’s fine as long as your charge controller and load are compatible with a 36 volt system voltage.

The other problem is that if one battery goes bad, you truly will lose the entire system. In the other two methods, if a battery goes bad, you can remove it and still run on the remaining batteries with normal voltage (although with less capacity). When batteries are in series, a failure could cause a total loss of power. You cannot simply remove the bad battery and continue at full voltage as with Methods 1 and 2.

System voltage will drop accordingly. In our example, a failed 12 volt battery in a 36 volt series means you’re now down to 24 volts. Voltage will dip below 24 volts if the defective battery itself becomes a load and drags down the others. Are your controller and load ok with that? Probably not.

So which method is “best”?

Whether to use a series or parallel configuration is largely a matter of personal preferences and the technical properties of your equipment. There is no “best” method. However, if you are going with a parallel system, wire your batteries as described in Method 2 above. The goal is to have each battery carry as equal a load as possible.

Resources.

Here is a very informative, easy to read web article that goes into detail about how small resistances can have a huge effect on battery performance. It also describes other effective connection methods. This website is worth bookmarking.

ICYMI, check out last month’s Off Grid Ham article for more battery tips.

Connection Method 2

THANKS,

And this is best said with capitol letters!

Noting your illustration # 2

I have been around electronics since my novice days in 1965.

Have worked only in electronics since then.

I have always connected in parallel, but I have never given thought to equal drain using method #2.

I am humbled.

Thank you.

Now I know why I have kept following you for a long time.

Little things, but very important.

Pete W6LAW

====

Hi Pete, it’s never too late to learn something new! Thanks for your nice comment.

Very good article, Chris. As I was reading I was happy you hit on most everything I was hoping you would. But a few additional points for flooded lead blocks plus some:

– Expanding a bank or replacing a weak/failed block: Oh, darn. Whatever the case, adding a new block(s) into an existing bank is sub optimum. The new block(s) will be limited to the least performing of the batteries when in series and the charging of them in parallel is not the best either. Special attention will be needed for charging practices.

– Starting vs deep cycle: Most starting batteries are the same because of their intended use could be in whatever equipment they might be installed but Deep Cycle batteries can vary widely by manufacturer. Some want higher voltages and some want longer absorb times. Some limit float time and some don’t even mention it. You need to follow the manufacturers specs for charging voltages and time for ALL THREE STAGES. Hopefully you have a good quality 3-stage charger specifically for deep cycle batteries and even better, one you can adjust the stages to the manufacturer’s specs.

– Your best battery friend is a Hydrometer. This isn’t something to fit into a short space. And be safe doing so.

Next is battery type. Sealed batteries charge differently than Flooded Lead Acid FLA). As above, deep cycle sealed batteries will have specific charging specs and are different than FLAs. Follow the manufacturer’s specs for sealed Deep Cycle batteries.

Lithium and lithium variants: Personally I love ’em for so many reasons. For the home I have transitioned to LifeP04. But the exception for all stuff, starting batteries, because of temperature restrictions where they are outside year around. They will get better and cheaper in time but not yet, IMHO. If off grid the last thing you want is a power hog heating blanket for the battery. ALSO, lithium stuff is highly manufacturer dependent and you REALLY need the correct charger for the block/bank from the manufacturer. You don’t mix or match anything lithium. And why would you after paying that price?

—-

This thread could go on for a long time. But we don’t need to duplicate battery wars here as there are so MANY places for (dis)information. The issue is what is GOOD information? The good information is that which is supplied by your battery’s manufacturer. Charging parameters and limits. Usage and maintenance. This is why I went with LifeP04. Maintenance is a memory. Self discharge is a memory. Charging below 50% SOC is a memory. Never do I run a generator at virtually no load to finish multiple hours of Absorb.

So you have to determine the pain point and application.

Well JR for sure batteries are a very complex topic and there’s no way we can cover everything at once.

It seems like the more I read up on batteries the more I realize how much I don’t know.

Thanks for the great comment!

Good information for anyone working with batteries, especially connecting to the + and – poles of the batteries at the opposite ends of the batteries in series. The other thing I’d add is that the cables linking the batteries should be as short as possible to minimize resistance and they should be the same length.

Oh, one other thing. A lot of LiFePo batteries have their own built in battery management systems. If they’re connected in series the first battery in the string might reach the proper state of charge before some of the other batteries do and shut down charging, which could leave some of the other batteries at different voltages. Every six months or so you may need to disconnect all of the batteries and charge them separately to re-balance them so they’re all at the same voltage.

Meanwhile planning continues on the “big” system here. Right now it looks like we’re going with 2-4, 48V 5 KWh LiFePo server rack style batteries (as many as we can afford) with a pair of EG4 6500 inverters in a split phase. Going to feed it with ground mounted solar panels for the time being. We need to get the roof done in a couple of years and at that time we’ll probably go to roof mounted solar panels.

Randy KC9YGN

Lithium batteries are their own animal and many off the time tested rules don’t apply, or are applied differently.

Good luck with planning your “big” system. It’s exciting and fun!

Series wiring has the advantage of being able to monitor voltage on each battery in the string. If you check often you’ll spot a bad battery before it becomes a problem. With DC-DC power supplies, inverters and surplus rectifiers plentiful going with -48 VDC is a pretty good option for hams. I recently bought an Ecoflow solar battery and gas generator to replace my old lead-acid Goal Zero camp battery. Internally it and the DC port of the generator run at 48 Volts. Makes for a much small gauge DC cable, and higher peak voltage from the solar panel input.

Eric, I’m curious about the Ecoflow and RFI. I have a Bluetti AC200Max and it puts out some serious RFI on the HF bands when I operate my transceiver from it. Not enough to prevent me from operating but enough to be a serious issue when trying to hear weak stations. And when I have my solar panels plugged into it it completely wipes out 40 meters. Does the Ecoflow cause interference as well or does it have a better design/shielding? Randy KC9YGN

That is an excellent point, Eric. Telephone companies run all their equipment on 48 volts DC and surplus gear does regularly show up at swap meets.

Pingback: Amateur Radio Weekly – Issue 279 • AmateurRadio.com

In your link ( http://www.smartgauge.co.uk/batt_con.html ), I would use Method #4. Each battery in parallel with that method has its current drawn through one short jumper plus one long jumper, equalizing the wiring resistance.

The drawing is for four batteries in parallel, I would have to think about how to wire 3 batteries in this manner.

Hi Tom, method 4 in the linked article is indeed the “best” way. However, the additional benefit over method 2 in my article is very small. I guess it all depends on how deep one wants to get into this.

I’ve been using method 2 for years (three batteries) with great results.

Thanks for your comment!

Very interesting and enjoyable article, thank you, but I think there must be a much more significant time difference between the USA and the UK than I realised. Unless the distance between the batteries is absolutely huge, over this side of the pond the “Connection Method 2” item would have been published on April 1st I think.

Hi Paul, I’m not sure where you’re going with your comment but I’m glad you enjoyed the article and hope you’ll stop by again.