Even many experienced ham operators will approach a table full of coax cable reels at a swap meet or stare at on line listings and feel lost in all the options, then out of confusion will default to buying whatever the vendor suggests or whatever is cheapest. They end up with coax cable that will probably work for their application, which is great, but the problem of not having learned anything remains. A familiarity with the different types of coax cable removes reliance on guessing and what others think is best for their needs and budget.

What exactly is coax cable?

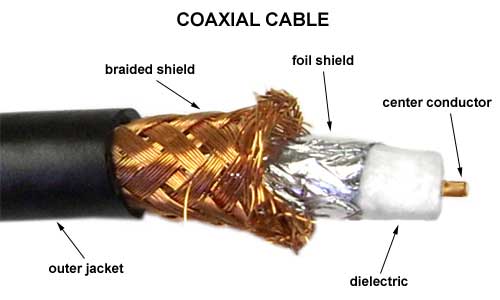

A coax, or coaxial cable, is a single conductor surrounded by a tubular insulator (known as a dielectric), which in turn is surrounded by a metallic shield. The package is finished off with a plastic insulator around the outer shield. The purpose of this arrangement is to keep the center conductor and outer shield the same distance apart so the cable maintains consistent electrical properties.

Coax cable nomenclature.

The term “RG” used to identify coax commonly used by hams has unclear origins. Some say it means “radio guide”. Other sources state that it means “radio-government”. The other letters refer to changes in specifications and standards for coax cable, except for the letter U which means “utility,” which I interpret to mean general purpose.

Example: RG-8U means “radio guide (or radio-government), #8 utility coax.” The 8 is just a random designator that does not have any direct meaning or follow any special rules.

The nomenclature systems for coax were developed by the government decades ago and have been revised several times. The radio amateur does not need to concern him/her self too much with the minutiae of coax identification protocols so we will not go too deep into it here. If you’re really that much of a geek about this stuff, Google “mil spec MIL-C-17” and have at it.

Meet the RG family.

RG-58 is thin (0.195 inch diameter) and ideal for short runs in tight spaces, such as a mobile installation. It is not recommended for home stations or runs greater than 25 feet. Most RG-58 has a solid inner conductor.

RG-8X is a popular middle of the road choice that offers the benefits of a smaller diameter (0.240 inch) coax without as much loss as RG-58.

RG-8 is a thick (0.405 inch diameter) coax that is more more expensive and more difficult to work with than the smaller sizes, but has the advantage of much less loss and higher power capacity.

Coax cable properties that radio amateurs should consider are line loss, shielding, stranded vs. solid conductors, velocity factor, and type of outer insulation.

Line loss explained.

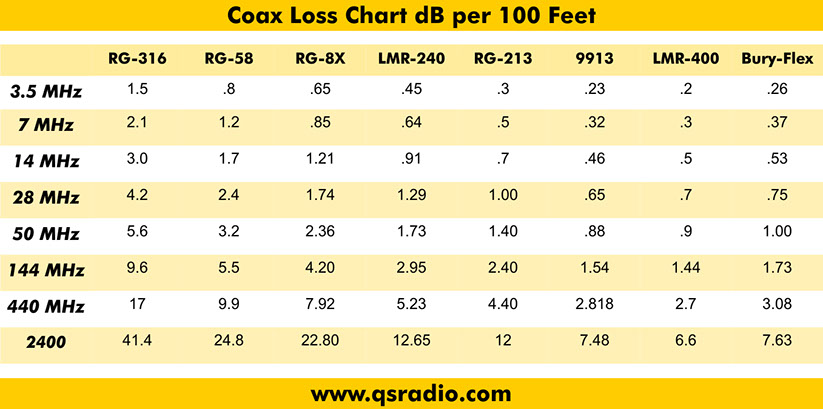

Line loss is the most important coax quality a radio amateur will care about. It is expressed in decibels (dB) per 100 feet and determines how much of your signal will “leak” out of the cable on its way to or from the antenna. The higher the dB loss rating is, the more signal you lose. 3 dB one way or the other represents halving (or doubling) the signal.

Example: If you put 100 watts into a coax feed that is 100 feet long and has a rated loss of -3 dB/100 feet at the frequency you are on, then you will have 50 watts left going into the antenna at the end of the cable. You have lost a full half of your power. You are also losing half of your received signal going the other way.

But suppose your antenna has a gain of +3 dB. The -3 dB loss through the coax and the +3 dB gain of the antenna cancel each other out. Your 100 watt station has an effective radiated power (ERP) of 100 watts flying off your antenna; you likewise have a break-even arrangement on the receive side.

Line loss is not a fixed value. In addition to length, the frequency of the signal has a huge effect on the overall loss of the coax. The higher the frequency, the greater the loss.

This on line coax loss calculator is a great reference I use all the time. It allows you to compute the effects of loss through different types of coax with any frequency, line length, or power level.

Also, any of the more advanced antenna analyzers such as the MFJ-226 will calculate the exact loss of any particular length of coax at any frequency. These devices are indeed expensive, but offer a lot of features for the money.

What you need to know: Always buy coax with line loss in mind. For very short cable runs (such as a mobile application), high loss cable may be acceptable. Antenna gain offsets feedline loss, yet you do not want to buy an expensive antenna with a lot of gain only to give the benefits away to cheap lossy coax.

Typically, a signal has to be either halved or doubled for the difference to be noticed by the operator one way or the other, so don’t get too hung up on squeezing every little fraction of a decibel from your system. A basic rule of thumb I follow is to keep net loss (including any antenna gain) at or below 3 dB.

Shielding is important, too!

Coax line loss is directly related to how well a cable is shielded. The shield is the outer braid of the coax and the more shielding a cable has, the fewer “holes” there are for RF to leak out. Even a tight braid is going to have tiny gaps. Shielding is usually expressed in a percentage. This percentage represents to what extent the coax is covered in shielding. A cable with a 95% shield means 95% of the cable is protected. The other 5% represents the holes.

Metal foil is sometimes used as shielding material. Since foil has no gaps, the shielding is 100%. However, a small amount of RF will still leak out through natural radiation. In these cases, foil-shielded coax will also have a dB attenuation value in addition to a percentage.

As already discussed, we want coax decibel line loss to be as small as possible. The exact opposite is true with the shield. The shielding decibel attenuation value should be as high as possible because the higher the value, the more effective the shield is at keeping the signal from leaking out.

Foil coax typically has an attenuation shield value of 90 dB or more. If every -3 dB represents halving the signal, that means 90 dB is an extremely effective shield that lets almost no RF go astray.

Example: Imagine reducing an RF signal by half. And then reduce the half by half. Do this 28 more times (for a total of 30 times, or 90 dB ÷ 3). Whatever RF is left after all that reducing is what leaks out as loss. Obviously, it will be a really, really tiny amount. On a 100 watt signal, a 90 dB attenuation shield will let the equivalent of only 0.000000093132257 watts leak out! That’s how effective foil shielding is.

What you need to know: Shielding effects how much loss a coax cable will have, and of course better shield adds to the cost. Foil is always 100% shielded (meaning no physical holes or gaps) and has a decibel attenuation value as described above. Braided shield is very close to but can never be 100%. The best shielded cables will have both foil and braid.

Velocity factor.

The speed of light is 186,000 miles per second. This measurement assumes the light is traveling in a vacuum. When light is not in a vacuum, it is slightly slower due to resistance from whatever physical medium it is passing through.

Radio waves also travel at the speed of light and are also slowed down by a physical medium, in this case coax cable. Velocity factor is is expressed as a percentage of 186,000 miles per second. Velocity factors can range from 66%-86%.

Line loss-shielding-velocity factor relationship.

When choosing coax cable I suggest focusing on line loss because lower loss cable by default also tends to have good shielding and a higher velocity factor. If the loss is low, then the other two values will take care of themselves.

Stranded vs. solid wire.

The center conductor can be either stranded or solid wire. The differences between them are not significant from a performance standpoint. Stranded wire is more flexible; solid wire is easier to solder a connector on. Which is “better” is largely a matter of personal preference.

Other factors.

When buying coax, It’s important to read the fine print and know what you are getting. Many types cannot be buried, or are not UV resistant. Many ham radio swap meet vendors do not know what they are selling, or will say whatever is needed to make a sale. Do your homework ahead of time and verify information by looking up coax data on your smartphone while shopping.

Specialty/premium coax.

For radio amateurs who have the money to buy the very best, here are your options from the RG-8 family:

Echoflex 10 & 15: Echoflex 10 has very low loss and will handle close to 4000 watts on HF frequencies. Echoflex 15 is larger than even RG-8. It’s a beefy 0.5487 inches in diameter and is the largest coax any radio amateur should ever need. It also has low loss and can handle over 6700 watts on HF. Echoflex is very expensive; it can easily run into hundreds of dollars to wire even one single antenna with Echoflex.

Echoflex cable requires specially engineered connectors. All common types are available (PL-259, etc) and are also quite expensive.

LMR-400 Ultraflex: Made by Times Microwave, Ultraflex coax is is very low loss even at UHF frequencies and will handle a lot more power than traditional cable. All that performance will cost you about double or more than standard RG-8.

And the RG-8 winner is…

DMR-400 by Davis is probably the best overall coax for amateur radio use. It has both a braided and foil shield, very low loss up to UHF frequencies, and can withstand almost any harsh exterior environment including direct burial. It is only modestly more expensive than lesser quality RG-8 cable and you do not need special connectors. The only thing I don’t like about DMR-400 is that is has a solid conductor. Still, it is an outstanding product that has perhaps the best cost vs. performance balance of any cable on the market.

Key points–what you need to know.

- Coax for amateur radio use comes in three main types: RG-58, RG-8X, and RG-8.

- Line loss is the single most important quality to look for when buying coax cable.

- High loss cable is usually acceptable for short runs, such as in a mobile installation.

- Shielding and velocity factor are important metrics as well, but if the loss is low, these issues will take care of themselves.

- Antenna gain and feedline loss offset each other.

- On line coax loss calculators are very useful tools that will let you compute the exact loss through any type of coax at any frequency or power level.

- Pay attention to things like UV resistance and suitability for exterior use and direct burial.

Choosing coax cable for amateur radio does not have to be difficult. While there are dozens of options, most coax falls into one of the three RG “families” described in this article. From there it’s just a matter of deciding what will fit into your budget.

Lots of good information in one short post. Thanks, Chris ?

Now THAT was an excellent presentation! Short, clear, and easy to understand. I liked the explanation of what’s really important, and what factors are ‘not so much’…

Thanks for the kind compliments, Ron. I really do try to make all my articles something anyone can relate to, no matter what their experience level. I hope you’ll stop by Off Grid Ham again, and pass the word along to your friends. I’m here for all radio amateurs.

The discussion covers 50 Ohms cables only. These are the right cables for transmitter use.

For purely receiving purposes I prefer 75 Ohms sattelite cable: Much cheaper and in many cases better shielding. Receiving antennas are most often not so exactly matched to the cable impedance and receivers often even less so – especially over frequency.

Dielectrica come in many forms. A solid dielectric is good if the cable is to resist some form of abuse. A foam dielectric leads to lower attenuation, but that mostly matters above 100 MHz or so.

BTW: The “charcteristic impedance” depends on the quotient of serial resistace (ohmic plus indictive) and the admittance of the dielectric (mostly capaitive). Threefore a 50 Ohms of some outer diameter has a thicker central conductor than a 75 Ohms or even 93 Ohms cable.

Alexander is right. I am only addressing 50 ohm coax. To keep it focused, I did not get into ladder line or the applications of 75 ohm television coax. Maybe I’ll address other types of feed line in the future.

Pingback: Assignment 1: End to End Communication – Jacob Brown: Communication Technology

A quick comment about LMR-400 (not the ultra-flex version, that’s different). I picked up a couple of 500 foot spools of the stuff when I got a real deal on it at an estate sale a few years ago. Great stuff but it can be very difficult to work with. It is *very* stiff, making it difficult to snake around corners, etc.

The stiffness also makes it a problem if it’s hooked directly to the equipment. You have to make sure it is bent into the proper shape *before* trying to hook it to the equipment. It can be so stiff that trying to move the equipment after the coax is connected risks breaking the coax connectors on the equipment. It turns into a lever, multiplying the lateral forces, and can crack or damage a connector before the cable itself begins to bend. You have to get in the habit of *always* disconnecting the coax before moving the equipment even slightly. I had to replace a few connectors before I learned that lesson.

One last issue. I don’t know if this is typical or if it’s just the batch I picked up, but there is some kind of lubricant or other substance on the shield that makes it very difficult to solder. I switched to using crimp connectors to get around that problem. Those seem to work at least as well as soldered connectors.

Thanks for adding to the body of knowledge, Randall.

There are several spray on contact cleaners on the market that will remove foreign substances from wire & coax to make it easier to solder. Solder flux is helpful too.